Word-struck Instruments: A Typewriter Poem Series

Many years ago, I purchased my first Royal #10 (“14 carriage) typewriter in Kelowna. An heirloom with too many woe-begotten memories. The kind that crushes lungs. Poetry, unequivocally, thundering.

I am struck by the crackling, sublime way the typewriter handles itself—and how other typists affectionately refer to them as “machines of living grace.” How one strike of a pin leads to another in the amphitheatre acoustics of my living room. Motivated by its music. Compelled.

For these reasons, I wanted to work with typewriters—lots of typewriters. I only own two, and I like the idea of writing poems for people’s typewriters. So I am calling upon my friends and extended community to lend their word-struck instruments to this deftest of causes.

Ink-led and loving as it is, to see how collaborating with one’s typewriter and myself can be restorative. And, within a newly blooming community of logophiles (word-lovers, collectors of our shiny artifacts of language), imagination flourishes as oceans to be.

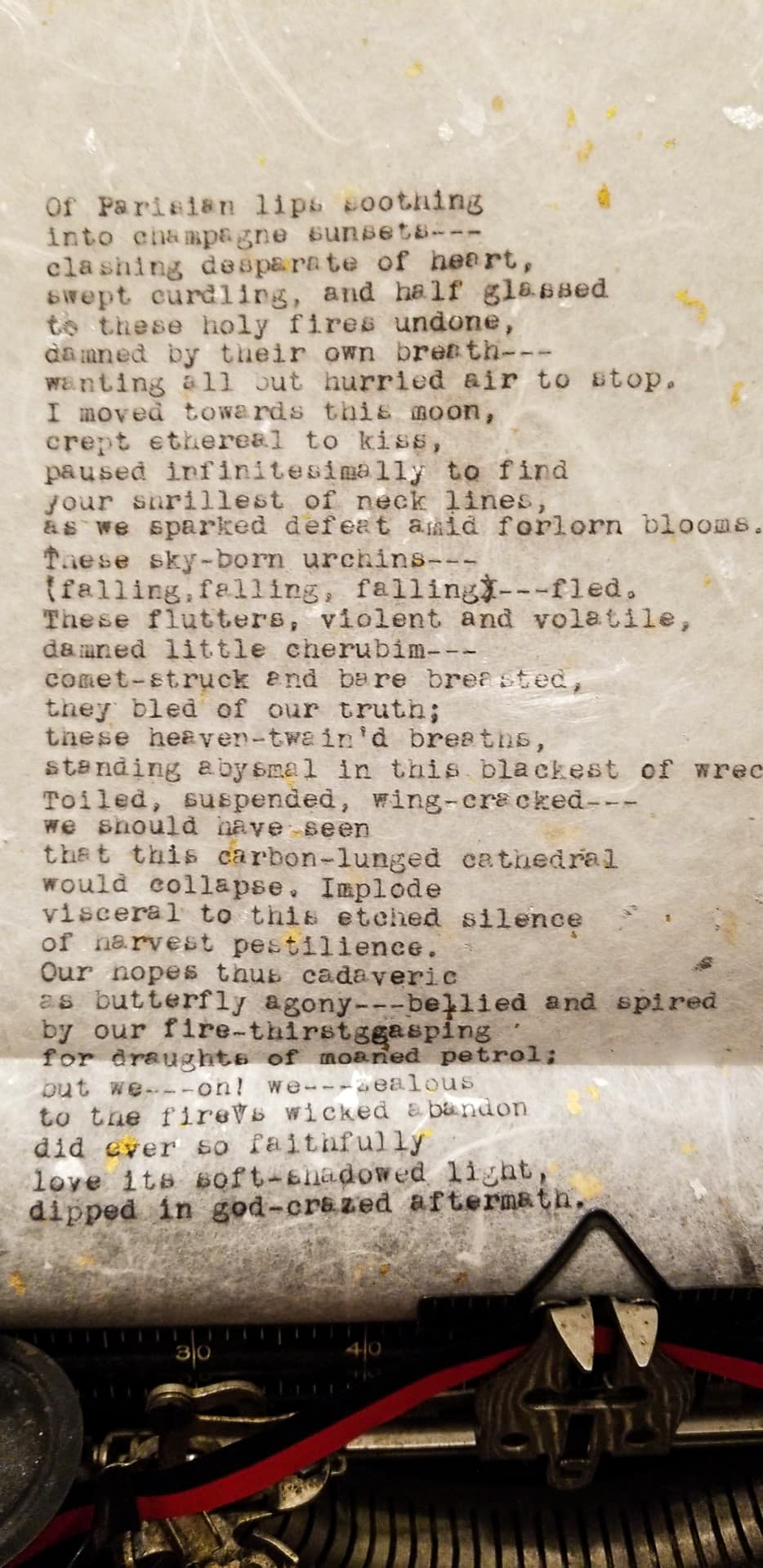

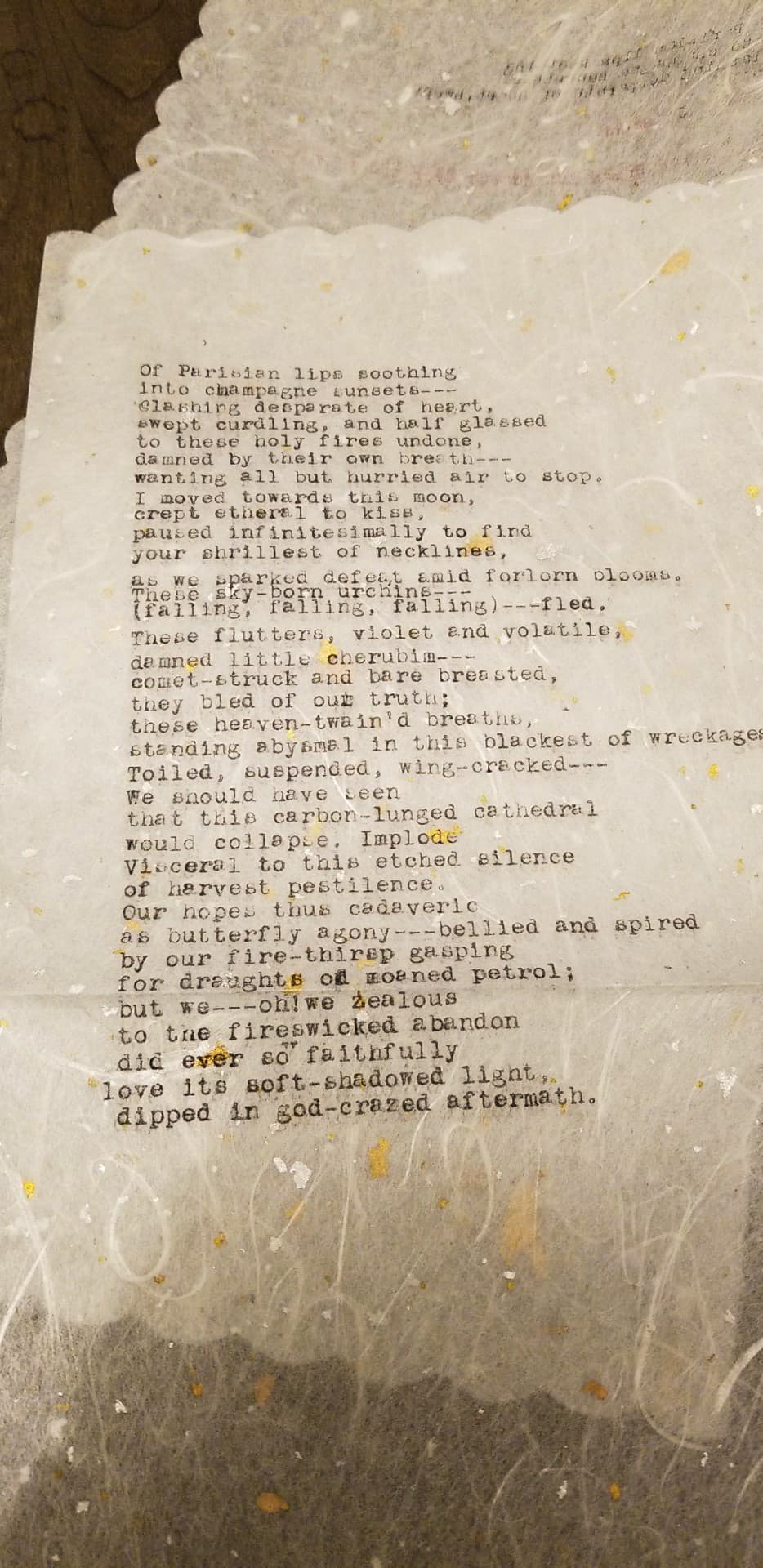

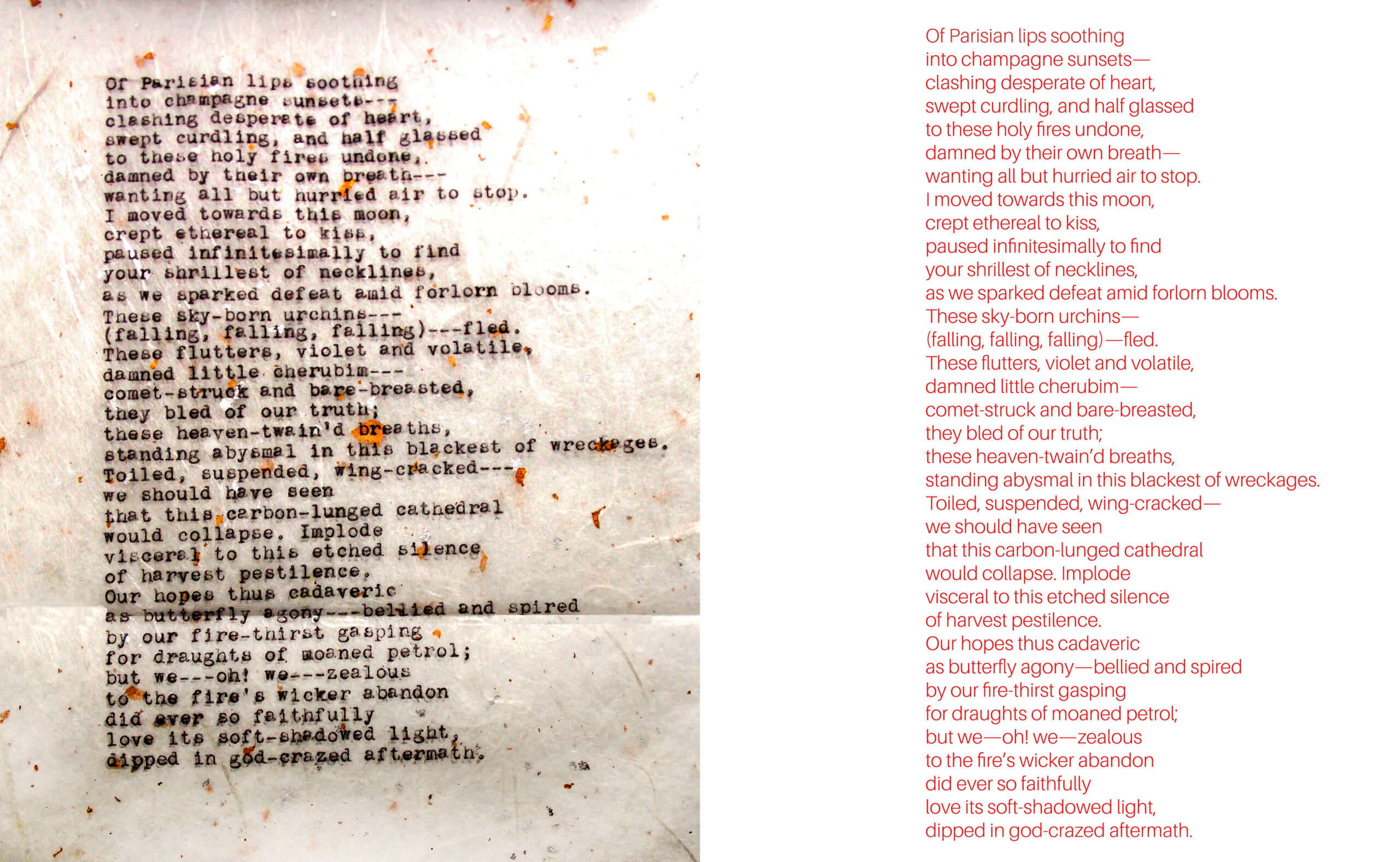

POEM – #1

INTERVIEW – Typewriter Poem #1: Corona – 1913, Joanne Taylor

Luke (L): I am so grateful that you accepted my invitation to be the first Typewriter Poem Series interviewee. Can you briefly let our readers know your understanding of what this project is and has been from start to finish? But, even before that, could you clarify how we know each other, and why do you think I may have hand-picked you for this project? And, if you would sneak in a few well-placed words about your lay glossing of my poetic practice and work as a poet over the years, that would be humbling. A little context will, I feel, go a long way to ease our readers into the space we have created by this interview exchange.

Joanne Taylor (J.T.): As I recall, you and I go back to a resplendent day. We were graduate students stationed at our UBC research quarters, perched on the Arts Building’s top floor – meeting briefly at the office fridge. A round of sauerkraut and kimchi were offered as a friendly gesture to learn more about my cohort. Little did I know, and to my great surprise, you were a wunderkind in waiting, leading me along this word-struck voyage towards inky artifacts. In that office, we spoke about our research, our committees, and what friends we mutually knew. The little teapot simmered to a full whistle, and we talked about social things too, like where we were from and where we were living, and if I remember, what our hobbies were. We planned to meet again as we had many things in common, not the least of which is our shared Doukhobor ancestry. Perhaps, some might even narrate us as kindred spirits in waiting. I am glad fate strung things so.

From that point onward, our paths crossed many times on and off-campus, and I am now quietly reminiscing about the many words exchanged during coffees, parties, and at evening poetry-performance meetups. We once organized an international road trip with another comrade to an anthropology conference. Ridiculous fun, memories. We often hiked to the top of an inner-city park mountain in Kelowna. Those were heady days indeed, always surrounded by long talks deconstructing this or that. But then you moved to Victoria to continue on your academic path, and I carried on with my own studies here.

As yours and my life continued to cross like the power lines, the ones I used to watch for hours on long road trips, there was a certain rhythm there. The metronome of its pacing just as mesmerizing as it was when I was a child on those summer trips, where each bundle of cables diverged between poles and then merged at the next junction. So too, I found does our friendship leap. It branches and forks out radially, always with multiple threads of poetry, travel, and academia being the constant connector back to the center. Time and time again.

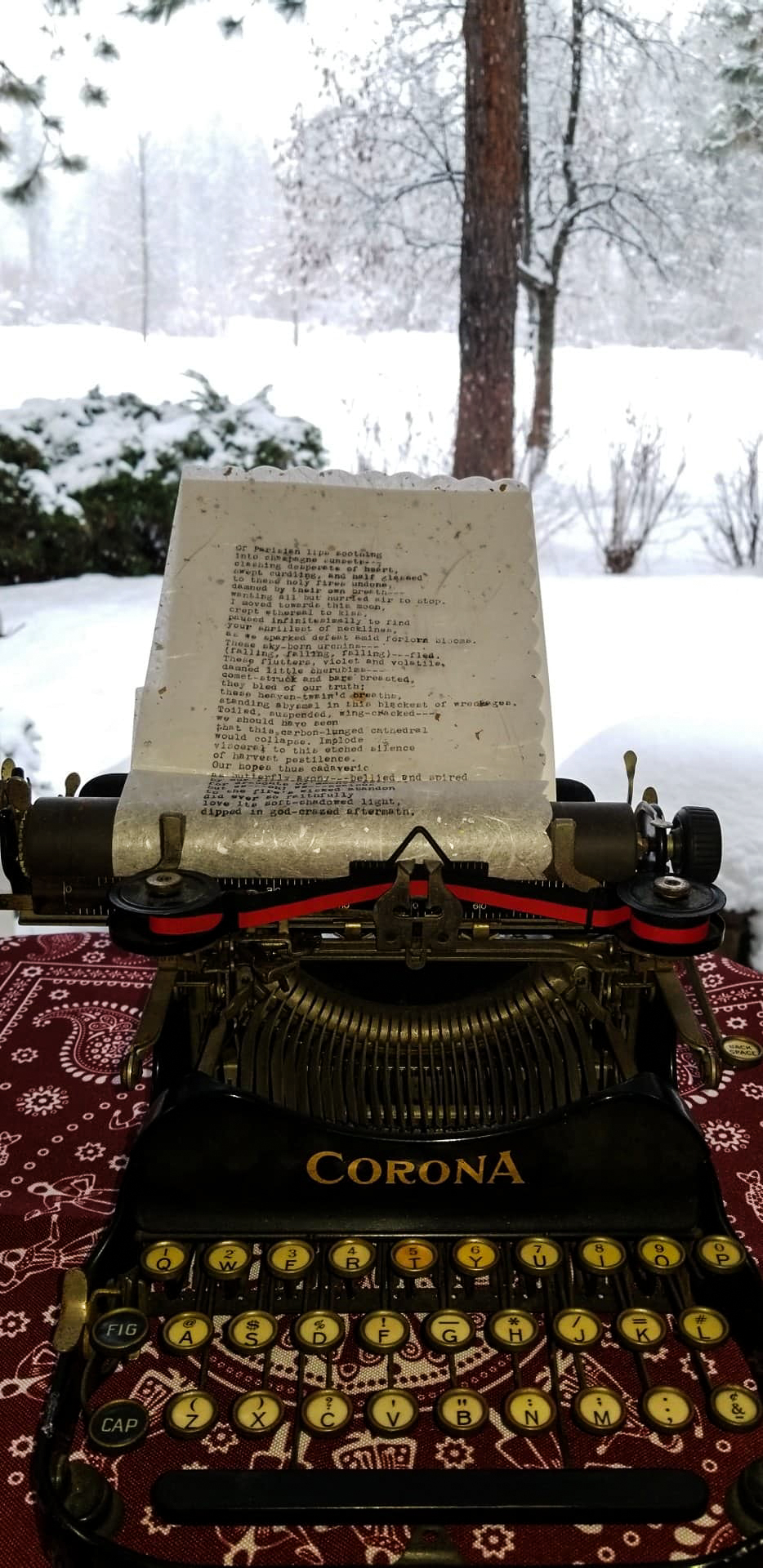

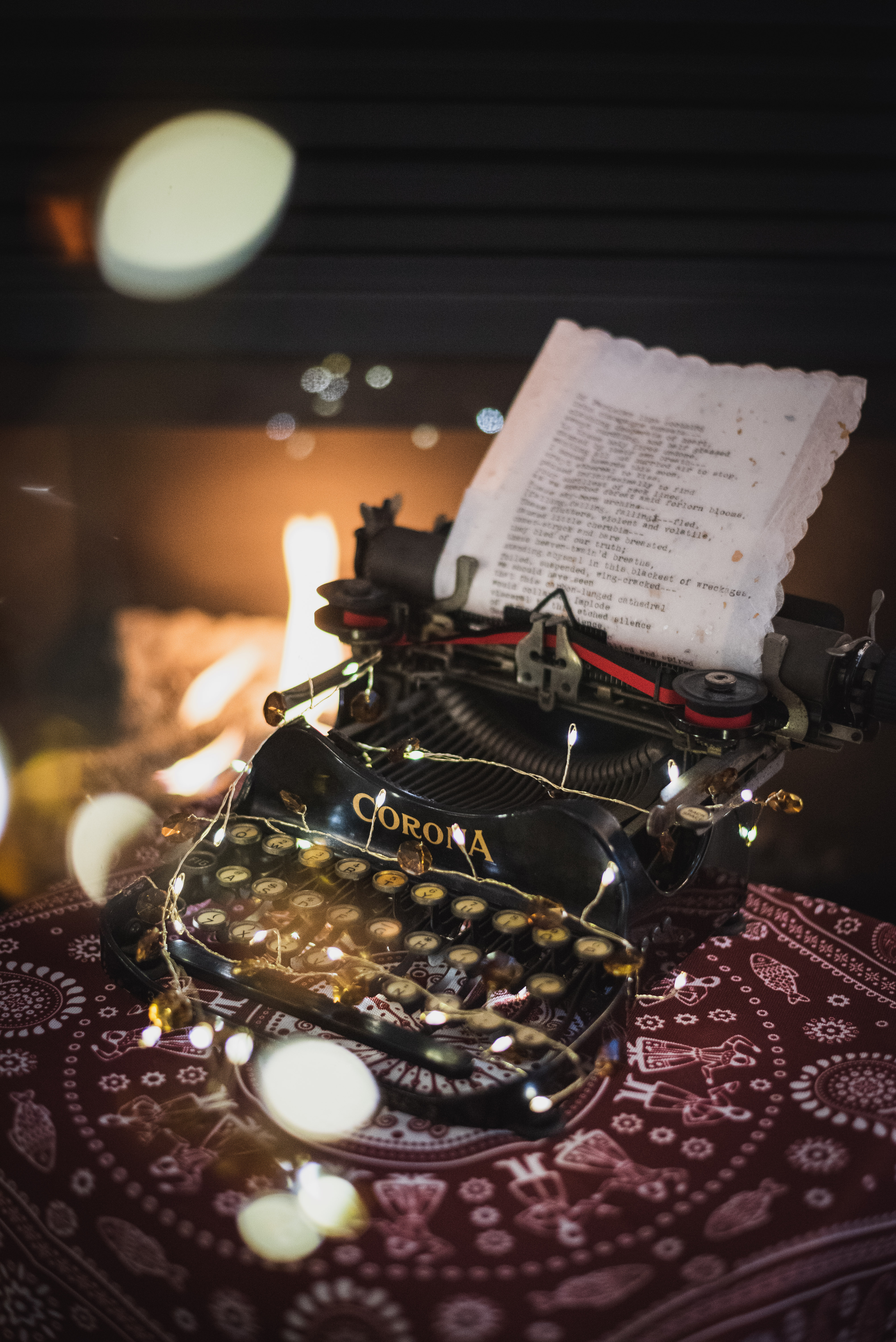

So, when you discovered that I owned a vintage Corona Typewriter, circa 1913, I became a natural choice as one of the first people you wanted to collaborate with on this poetry project. It catalyzed an uncanny feeling. With each step, haunting turn, and cling of words, serendipity greeted me. Those tomes and tombs of association were heralding each and all of us. I cannot explain it entirely as I was and am still merely a wandering bark in this timeline. And, as most stories begin by calls to action, another good friend of mine got in touch with me. She was staying in France at the time. Heart-lept to whimsy, she invited me for a quick crossing to Paris. I was to assist her in exiting from Paris, that global epicentre of art, culture, history, and, of course, the noblest of gothic cathedrals, Notre-Dame. So on that bright thread, I flew away to spend the last few days of her quiet sojourn in France together – grabbing overflows of coffee in one of Hemmingway’s haunts as we watched the steam of it all curl into the sunset.

Once again, our lives converged with the burning of Notre Dame soon after my trip to Paris. The world watched, flickering lights on screens re-enacting the tragedy for prosperity. As if moths were eating those silent rectories of the mind, the ground stood shaken. You wrote the Notre-Dame poem, and I, with my typewriter, became the willing conductee to this orchestra. I typed your words of love and burning alongside a fresh and still-beating memory of being in the Dame with my travel companion, Ellie Colet, not too long before its demise.

I knew you wrote the most elegant of poems, such as when you shared with me a sonnet you had written to a Russian woman, Lala Ragimova. Your words bled forth and transcended time, I felt, as this timeless practice often does, gilding over our un-savoured mortal existence. You knew then how the alchemy of poetry might offer its own panacea for existence. Poetry leans into these strange passions. I had such an experience in my youth. In my early twenties, I worked as an office assistant where an executive was quite enamoured with me. On one occasion, I returned to my office after a lunch break and found a beautifully hand-written poem on an edge-crumpled piece of parchment paper. Stunned, I was surprised as I read the words – and more importantly, that someone was watching me, clocking in my every move to see when I returned to my desk. Oh! to have that youthful innocence, that raw exuberant burst of love displayed for me upon my return. My wild heart beat, as my face flushed. As if I were needled tenderly by this aphrodisiac, swept by word promises. I kept that paper never fully knowing or inquiring who the author was. Eventually, I lost the poem, that symbol of an innocent sentiment that spoke brilliantly of and delved headstrong into a bottomless ocean of love-crushed gazes.

Now, as much as this lingering memory nips, I must come back to your initial questions. Ah, “Typewriter,” you say? What does this have to do with poetry, Notre Dame, and friendship? The knotty confluence of life flowing together, I suppose. You and I both tapped into and were immediately drawn by this vast cultural moment, finding together a way to merge your poetic prowess and my ambling steps through Paris to re-live that horrific experience. These lived materialities resurface to depict a stark loss to our collective world history in (re)witnessing the Dame’s burning. We talked over this poem for more months than I would like to admit. Still more yet to uncover with each relining of this story. We bonded betwixt and between a passionate appreciation for that writer’s tool, the anthropologist’s symbol of the ethnographic recording of history, of which I happen to have – the typewriter! So, perhaps, the behind-the-scenes narrator of life would say that a perfect and quintessential incorporation of poetry, history, culture, and friendship formed along the way to make this moment happen.

And, on this particular sun-drenched spring day, this lovely Corona typewriter caught my eye, as it was misplaced sitting alone, calmly juxtaposed against all of its ancient Japanese brothers and sisters.

L: Can you explain your connection and history to this Corona typewriter? Elaborate a little for us.

J.T.: Well, it is a bit of a circuitous route that this lovely typewriter came into my stewardship and most recent use. While living in Japan, I would often wander the Japanese craft markets, which were often a sight to behold so raptly. They were not your average street markets. Rather, I felt their shimmer as lovely anthropological displays of rare swords (yes, the ones used for seppuku and hara-kiri), ancient shodo, antique imari in the most beautiful of faded colours, lovely old raku from the Edo era, and washi paper made into uniquely shaped books. Let alone the countless other everyday steam-dried items that were carefully arranged on blankets on the ground by its owner. And, on this particular sun-drenched spring day, this lovely Corona typewriter caught my eye, as it was misplaced sitting alone, calmly juxtaposed against all of its ancient Japanese brothers and sisters. Ah, a western piece of history. As I walked closer to it, I noticed that it was actually in excellent working condition. So, after a wee bit of bartering – the Japanese do not like haggling – I bought it for the modest sum of ¥2,000 – about $20 Canadian at the time. It lay stored in a box for roughly 20 years as my husband and I continued to work in Tokyo and finally returned to Canada to raise our family. About four years ago, while preparing to move into a new home, I decided to unpack it and put it on display. Luckily, you gently urged and prodded me to service it in Toronto, and when it came back, I began typing the poem that accompanies this story of a lost treasure found again. P.S. My entrepreneurial son now uses the typewriter to write thank you notes to his clients on little pieces of cardstock. Such a lovely touch. Thank you, Luke. And the Corona, thanks to you too.

L: What did it feel like to type again? The sweet cadence. Can you give us a sense of the materiality and process of the typewriter? What stood out for you?

J.T.: At first, the keys were like hitting iron-reinforced concrete… like rebar or something cold and hard. As I got my strength back into each finger, I noticed a certain satisfaction of hitting each key with an assertive power that dominated the keyboard. It took a while to learn the old 1913 custom of three levels of symbols on each key, and, of course, knowing how to move the bar along and the page advancer thing. That learning curve was a bit tedious as I tend to be impatient with learning new things. But I loved the process of typing the poem over and over until it became a masterpiece of sorts. That final type-written version and the final five or so copies became a Zen experience: each morning, I tackled the process, alerting my brain cells to wakeup to the newfound habit of typing on an old Corona Typewriter. It was like, oh, I cannot wait to start typing. I really miss that and hope to do something like that again. Hint, hint?

L: Can you mention what creative and meditative effects were present for you in working with the poem? How does it continue to shape your thought process from inception to now? Earlier, I involved you in its collaboration as you were part of editing and giving feedback on how the poem was written and then you became an instrument of its material mediation as you typed it into reality. How did working with poetry in this manner animate your imagination?

J.T.: That is an interesting question that deserves some discussion on the process between inception and completion. Really, two processes fused together at some point. What I found was that I did not know where I was going with the poem. I wondered when we were working on it together. That was a learning activity in itself. As I think back to the editing process, I believe that I was simply an editor and not a poetry writer, or poet. I was not involved in the initial conceptualization of the poem. That was left up to you, the poet. At this point, I considered myself a bystander who assisted the poet in completing the poem.

Now, for a moment, if you will imagine the tables completely turning, literally and figuratively. For the typing of the poem, I became editor-in-chief. I saw the poem in a different light as I transferred the written word to a much deeper cognitive state of affective comprehension and appreciation. I noticed words and sentences that I did not recall in the early editing process. I interpreted words and phrases differently, and I came to understand the poem in its totality. As I entered the words, my subconscious understanding of the poem’s meaning became more firmly embedded within my psyche. The Japanese have a saying that one must master the art until it becomes Zen, which is to say that the art transfers to a deeper part of the brain from the analytical learning part, to become so subconscious that the artist is not even aware of their actions. As I typed the poem daily to achieve the Zen-like embodiment of the poem, I became part of the poem; in essence, I know this is a cliché, but I became one with the poem. I was in Paris and could feel the heat of the embers – “to these holy fires undone” – and could visualize the fire in my mind as I released the words. Soon, I believe I memorized the poem, and its unique prose and style such as “(falling, falling, falling)—fled” burst. I no longer needed to look at the poem but knew instinctually how to type those words and their accompanying unique punctuation, a truly sublime feeling of Zen mastership.

Somewhere, these words are stored between the synapses of my grey matter, adding to the already storied texture of my life. Brilliance, moments dashed and recollected. I hope I will never forget them.

L: Can you describe further what it feels like to have a poem memorized? That your mind has, in a sense, taken on a shadow tattoo of sorts. Do you think that these words have a special calling to you now that they have been collected and recollected inside your intimate thoughts?

J.T.: Memory is a beautiful thing. And memorization is a delicate process. In my youth, I recall having to memorize Shakespeare – and for fun, to write and remember a poem of my own. I was so encouraged to randomly throw words together that sounded so elegant that I went on a poetry kick, writing anywhere and anytime I could. Yet, my youthful foray into poetic writing was short-lived, and life’s enthusiasm gave way to other interests. Our brain is continuously processing and recording and memorizing. To consciously remember and test our memory is another thing altogether. I was happy to recollect the joy that memorizing brought me many decades previously. As I typed the poem over and over again, I found, to my great relief, that my memory still served me. Though, if I am honest, my memory does fail me on occasion, more than I wish to admit. Memorizing the first two lines, “Of Parisian lips soothing [/] into champagne sunsets,” seemed so easy. As the days of typing progressed, I was eager to see the subsequent lines fall easily into the crevices of my mind. Somewhere, these words are stored between the synapses of my grey matter, adding to the already storied texture of my life. Brilliance, moments dashed and recollected. I hope I will never forget them.

L: How do you imagine the poem will change your relationship with Paris when you go back? Or when you daydream of sauntering its streets? How does poetry extend your spatial awareness? You also mentioned that you found the typewriter in Japan. Did your recent trip to Japan alter how you relate to your Corona and the poem? How might poetry reorient one to the world?

J.T.: My dear friend and intrepid travel companion, Ellie, and I are already planning our next trip to Paris and its environs. She studied French literature there in her past graduate days and is completely fluent in French and the Parisian dialect making a trip to France an unforgettable experience. We navigated boulangeries, grand magasins, épiceries, le marche, charcuteries, fromageries, patisseries. Yes, we even went to Sunday mass, there, in Notre Dame, on that snow-driven morning, not knowing that it would be our last in her beautiful cathedral, under her gothic spire that soon fell that fateful day. We will be sure to attend mass again in the new church next year, or the year after, when the French finally say “c’est finis, n’est pas!”

Ellie and I certainly had our fair share of sauntering the Paris streets in the beauty of the cold February wind. This instance was a different experience than when I travelled to Paris with my family on three separate occasions, and different than the first time when I was just 21 with my grandfather visiting relatives in the old country, Russia. It is unusual in that I had much more freedom to do and see what I wanted without having to think about whether places were appropriate for young children or my husband. It does sound a bit self-serving, but it is true. With my travel friend, we aligned well with where we wanted to eat, shop, and stop for afternoon coffee. So many beautiful, spontaneous experiences as she shares the same energy and enthusiasm for exploring the unexplored – those out-of-the-way places – the underground archeology sites; the crypts; the Roman Baths; or their quiet, mundane back-alley cafes where chance conversations with French locals were born and easily navigated. Like poetry, these daily excursions were not necessarily planned. Instead, they were allowed to unfold as we came upon areas that were just too wonderful to pass by at once: a little bookstore, a linen shop, an antique stationery store, the Grand Galleries Lafayette to window shop.

Poetry allows the mind to lean into the areas of passion, love, life, and death that our rational minds usually do not venture towards in haste. Like travel, we dove into the not-so-often-imagined lives of the ordinary French. Poetry does that too – when we allow ourselves to explore subjects we do not usually think about thoroughly, we can begin to express these moments in poetry creatively. Our walks and talks took shape, showing us new life inside the poetic exuberance that each map and musing of our daily journeys conjured alongside the unknown. The Dame, I anticipate, stands as a symbol of our last trip, and this poem will be a welcomed bridge between the memory of the spire’s grandeur and our next trip there. Yet, unlike this poem’s connection to Paris, my typewriter did not play equally into my memory, daydreaming, and reorientation during my recent trip to Japan – despite having purchased it for ¥2,000 so long ago in that quaint, Japanese market. Perhaps, this sentiment holds true for me because the typewriter does not as effortlessly embody and evoke the meaning of religion, friendship, and travel to that specific geographic and cultural context, as did my last trip to Paris and its sharp re-imagining through the eloquent lines of the poem. (We may still yet have to test this theory by collaborating on another poem, one with Japanese form and content!) Poetry allows one to reorient oneself into memories, past and future. It parallels both the physical and the spiritual experience of travel, exploration, friendship, and history – at once challenging these imaginings into becoming a living place, and likewise, into the creative, mindful exercise and expressions of poetry making as one’s heart unfolds onto the landscape.

When tears are too much to bear, the words strung together like stars in the night sky can explain how to re-engineer a hopeful, kinder world in which we once again can whisper within the breath’s proximity, I love you.

L: While this world of ours is presumably filled with madness, how do you think poetry can aid and arrest it to health? What do humans have to gain from indulging in all of these imaginings?

J.T.: Well, in times like these, poetry can help us to imagine a better future and to re-imagine the past – to think upon times that just a few short months ago seemed effortless and carefree. That is not to say that the world is not rife with racism, war, poverty, food insecurity, climate change, and rampant inequality. But, if we had only known then, we could have stalled ourselves to savour those bittersweet moments that we are so privileged to have felt, that one last heart-rending hug, or dinner, or tea with friends. Let the kiss linger. Perhaps even sonder inside the fluid energies between people passing in a hallway or the bistro where friends might meet. Poetry can allow us to pause, expressing those once liquid and bright feelings using words and styles that legislate its use to tell the beauty of those times. Poetry can help us write the future hoped when emotions are too intense and severe to speak but will otherwise encourage these feelings to pass through rhythm, sound, and cadence – that which evokes the love and loss from those all-too few and short days we squandered to vertigo. When words become channelled through one’s inner geography, generations can look to these poems as historical embodiments of the trauma and crisis that was felt like a global heartbeat. Of this pandemic’s syncopated horror, for example. When tears are too much to bear, the words strung together like stars in the night sky can explain how to re-engineer a hopeful, kinder world in which we once again can whisper within the breath’s proximity, I love you. Poetry stands as a symbol of history, right or wrong – and it can take us away to un-moment the despair of the world, or in our hearts. In our supreme instancy of lockdowns (jammed by being so impossible), think where would we have turned to if not to the words? A lone heart clacking and crying for poems, the arts, music, song, dance, and paintings. Where does this chained beauty go to die? To surrender spirit? To words and poems, un-conceded, unadulterated, vulnerable, of course.

L: Truth. Where can people find you? Do you see any relationship between creative pursuits and your academic craft? As an anthropologist and a human being, where would you apply poetry? Have you considered writing typewriter poems by the river and gardens that you research?

J.T.: I am not on social media, much. Nor am I someone who has created their own website. It seems that I have shared my life on platforms like Facebook and Instagram. People can find me through email too. I sometimes haunt local coffee shops in Creston as I often run off to see a friend, grabbing a tea and scone to settle conversational scores light-heartedly. And to the jagged-edged mountains of the Himalayas or the Rockies, to the smaller yet equally majestic local hills and mounts. These days I am mostly with my Mother and family, who have gathered around her. As time rages to pass, I would hope that some people’s hearts have found a special place for me. Perhaps inside my words or silent feelings that I have imparted to a few. Perhaps inside my wisdom to shoulder friends. Perhaps my words are my poetry. Even a snakebite of this sentiment settling inside my research and writing, my ideas, my thoughts, and my plans can speak volumes. I would love to be the Ondaatje of our time. No cares at my back, clad with a typewriter in tow, as I power hike inside a canyon or down a crevasse to a babbling brook. Time itself suspended on a riverine walk, stopping adrift as I stand by a single mountainside creek to ponder existence, children, parents, partners, love, and the cycle of life. I would like that very much, along the Kootenay River in its neighbouring Kokanee Glacier Park is where I would go.

L: Thanks for being such a patient and keen collaborator! Is there anything that we missed talking about and left unsaid? Do you have any questions for me? Let your imagination run wild here before we hit the iron curtain of our hour. What do you think you took away from all this?

J.T.: As I enter these later phases of my life, I take special note to walk and talk a little softer, to love more profoundly in feeling the Earth’s force upon me and those loved friends and distant acquaintances alike. To open my heart and sensibilities to redressing the injustices of life. I do realize – that for a few short moments – we are gifted with this time on Earth. We should love more, breathe with conscious eloquence, and reject the seductiveness of the world’s vortex and its energies as it does not allow those spaces of love to shine its light through easily. Virtue exists as we learn to hug the dying without hesitation, to say out loud the memories we have treasured, to give time without expectations of return, and not to cry but to understand and accept that light and energy are always here inside the constellations of our universe. In the end, we are all bound together in light and love as we are set astray in a little place we call life. I ask of you, what would you do if you had three months to live? What would you say, and who would you lovingly utter it to in earnest? As has been clamoured a many thousand times before us, how would you live those three months fearing the lone drop of the final curtain of your last hour? From these deep questions of love and life and my own need to express myself, I have felt a bonded connection to poetry, my typewriter, and, most importantly, to a kindred spirit and meaningful friendship. That is all for now, my friend. Our poetry, writing, philosophizing over questions without answers will continue with ease. Over and out.

Fractured, invisible –

bits of our being are always

in a state of mourning.

L: I can already imagine what that would be like as far as the first two questions. The last being trickier to encapsulate in words. This exercise reverberates across fields of human experience. Perhaps, dipping one’s consciousness further into mixed discussions as impactful as poetry and spirituality – anything from Cavalier poets and their daft contemplations of Horace to Tibetan Buddhist enactments of maraṇasati (“mindfulness of death”). I once thought I knew what death was, but I can only escape to it in approximates. Many years ago, another graduate student gifted me Jon McGregor’s Even the Dogs. That text follows this meditation inside the visceral death spaces that trickle across our urban and existential experiences. The way McGregor reframes the reader to ponder over the death event is itself an invitation to better understand how life might brutally and at once breathtakingly move on without us. Whispers hurtle what was a life forward to the next precipice. Fractured, invisible – bits of our being are always in a state of mourning. That emotional sequencing, as hard as it is to swallow, is what resonates across the prose-poetry text and the scars that touch upon us as we move through its fire. I will have to reacquaint myself with McGregor’s prose elegy. Say a few last words for Notre Dame. Within the stain of it all, I see this death stamp within the social life of things. There is also a movement within the typewriter poem, I would argue, that speaks to the human psyche wanting death, an ending. Partly, this aspect of self-destruction belies how the structures we erect are imminent and primed for collapse – that the aftermath is the heart-space upon which rebirth can settle within the rubble of Ozymandias’ feet. To be humbled by this full-bodied toil (and the weight of existence) falling as brilliant spires of fire. Scorched, it stirs forth as the ontological forest finds new expression in the timbering, tamberous sounds of its undoing. Later, a lone archaeologist of the soul waits to wade through and decipher what we once called a life.

To answer your questions more directly, I would abandon what work I had with a notice of only three months left. I would stop living for myself – as the fullest idea of what an accomplishment is shatters to infinite dust. I would write some final poems, plant a few things, and journal out the remaining days I had to leave a small impression on those who knew me. I think, if anything, I would see what I might be able to do in terms of making a fleeting but kind impact on the future (as the only thing that matters then is a sense of generations and how they echo forward). I am not so vain – nor even attached to my enactment of self – to think that anything I would do could be of lasting effect; I am at peace with the universe taking pause to forget me completely as time, light, and love funnel to farewell. We need to leave space for other stories. And, if all of this is true, the real question then becomes why we do not make extra affordances and time to thread our lives with such wonderful intent and ethical relations. Are we, in fact, out of integrity with the seasons of ourselves when we ignore the wisdom of this death-self and the darlings of our lives (family members) who wish to teach us these things in their passing(s)?

I confess that I will afford words – bright effigies to silence. What needs grapple us to such edges of bereavement find form and disaster within this language of what has been unsaid. I cannot speak in pure absences but inside premeditated solitude as the typebar clamours storms against the wheels of Dharma. Inked – I release to expression. I feel that poetry as a way of being can blast echoes through the invisible tyranny of our lives. To rest at a point of love and rage. My friend, in all words, I thank you for this exchange. To other stories, music calls me towards these vivid machines of living grace. To pour.

IN-PROCESS IMAGES

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWEE

Dr. Joanne Taylor is a white settler of primarily third-generation Russian descendants who grew up on unceded Coast Salish, Ktunaxa, and Syilx territories, Vancouver, Kootenay-Boundary, and Kelowna, BC. Taylor is currently an environmental anthropologist and political ecologist and received her Ph.D. from the University of British Columbia Okanagan in the Department of Community, Culture, and Global Studies. Funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), Taylor’s doctoral research investigated food security and food sovereignty in the traditional lands of the Ktunaxa First Nation and the Yaqan-Nu?kiy of the Creston Valley of British Columbia during catastrophic climate change and the renegotiation of the bilateral Columbia River Treaty. She foregrounds from multiple perspectives how food security and food sovereignty continue to be dominated by violent resource extractive policies and power dynamics that marginalize Indigenous food production and small-scale food producers. Her work asks why the path to seemingly straightforward food security is so densely obstacled. As part of this exploration, she asks how Indigenous food paradigms might commandeer policy that serves to establish a just, food-as-a-human-rights reality. For this pursuit, she worked closely with Dr. John Wagner, Dr. Hugo De Burgos, and Dr. Mary Stockdale at the University of British Columbia, Kelowna.

Joanne is currently Lead Researcher and SSHRC Post-Doctoral Fellow at the University of British Columbia Okanagan in the Department of Economics, Political Science, and Philosophy, under the guidance of Dr. John Janmaat. Her fundamental research focus is on agricultural adaptation to climate change in the Cariboo (Secwepemc) and Okanagan (Syilx) Regions of British Columbia. This critical and relevant research resides at the intersections of food, climate change, and water in the interdisciplinary fields of environmental anthropology and sustainability with a focus on the complex and myriad ways food security and food sovereignty are defined globally, nationally, regionally, and locally.

Joanne lives in Kelowna, BC with her family and enjoys skiing, hiking, yoga, gardening, cooking, and travelling within British Columbia.

Note on Photography: Photos for this Typewriter Series #1 post were taken by Nikita Taylor (https://www.nikitashoots.ca/) and his family.

Footnote: The interviewee’s Mother passed into the light just after this poetry interview was complete. For her, the life lived was a poem in constant evolution, shifting here and there throughout the universe of which she is now a part of its celestial sphere. She shares her love as though etched into her friend’s and family’s hearts, spun like magic firewind waiting to release its crystalline words throughout the universe. Until we meet again, and our dust collides into light, I will remain your loving daughter.